Ash Trees—a Celebration and a Lament (JMU 2020)

The Ash tree is one of the most important riparian plants in North America. In Eastern North America there are, or were, three common species in the Fraxinus genus, the White, Green, and Black Ash. In the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, Green Ash is one of the most prolific trees along streams, river bottoms, and wetlands. Unfortunately, Ash trees are disappearing from the American landscape. All three of the aforementioned ash tree species are critically endangered because of the nonnative Emerald Ash Borer.

A young, healthy Green Ash in Swoope, Virginia, at the intersection of Trimbles Mill Road and Boy Scout Lane. Photo by R. Whitescarver 7/19

These trees thrive near water and even tolerate the harsh conditions of urban environments like road salt and heavy traffic. They have been extensively planted along urban streets in America and abroad.

Ecosystem Restoration

Ash trees are special because they can restore natural systems. They readily colonize riparian areas where their roots help stabilize stream banks, their leaves feed both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, and their branches provide shade and nesting sites for many animals.

When we fenced the cows out of the Middle River on our farm, Mother Nature planted Green Ash trees by the hundreds in the buffer area between the pasture and river.

Healthy Green Ash tree with seeds. Gravity, wind, and water disperse the seeds. Photo by R. Whitescarver.

The trees were so thick I had to thin them out. We call these trees pioneer trees because they can populate an area on their own; you don’t have to plant them as long as source trees are nearby.

Growth Performance of Many Animals Best With Ash Leaves

Ash leaves are a critical food source for American frogs. The growth performance of tadpoles is better with a diet of Green Ash leaves than with Red Maple leaves according to research published in Freshwater Biology. As Green Ash disappears from the landscape, Red Maple fills in. Tadpoles and perhaps many other species that trive on Green Ash leaves will be negatively affected.

Both White and Green Ash leaves are some of the most nutritious and important foods for leaf-cutting and shredding aquatic insects. For example, two species of Mayflies studied in White Clay Creek in Pennsylvania grew best on a diet of White Ash leaves. Some Craneflies and Stoneflies also showed better growth performance on White Ash leaves than on other species of tree leaves studied, according to Dr. Bern Sweeney‘s research published by the Academy of Natural Sciences.

Ash Wood Is Unique and Has Quite a History

Ash wood has some special qualities. For guitars, it is soft enough to work easily and has large open pores that according to the Fender website make it “remarkably resonant and sweet-sounding, with clearly chiming highs, defined midrange, and strong low end.”

Leo Fender introduced the Telecaster electric guitar in 1951. Made from the wood from both White and Green Ash, this guitar had a new sound that broke the barriers in rock, country, and blues music. When you hear the sweet-talking guitar sounds from Keith Richards, Elvis Presley, Eric Clapton, B.B. King, and Buck Owens, they were probably coming out of a Fender Telecaster.

The Fender Telecaster electric guitar debuted in 1951 and was made from Ash wood. Photo from the Fender website.

Preferred Wood For Baseball Bats

Ash wood has another special quality. When a baseball hits it, it compresses and sends the ball away with a “trampoline effect.” That’s why many of the famous Louisville Slugger baseball bats are made from Ash wood. White Ash is preferred but Green Ash is often marketed as White Ash.

Louisville Slugger baseball bats like this one are made from Ash tree wood, many from Green Ash which is often marketed as White Ash. Photo from the Louisville Slugger website.

This wood is also popular in flooring, millwork, boxes, crates, baskets, and tool handles.

Emerald Ash Borer Discovered in Michigan in 2002

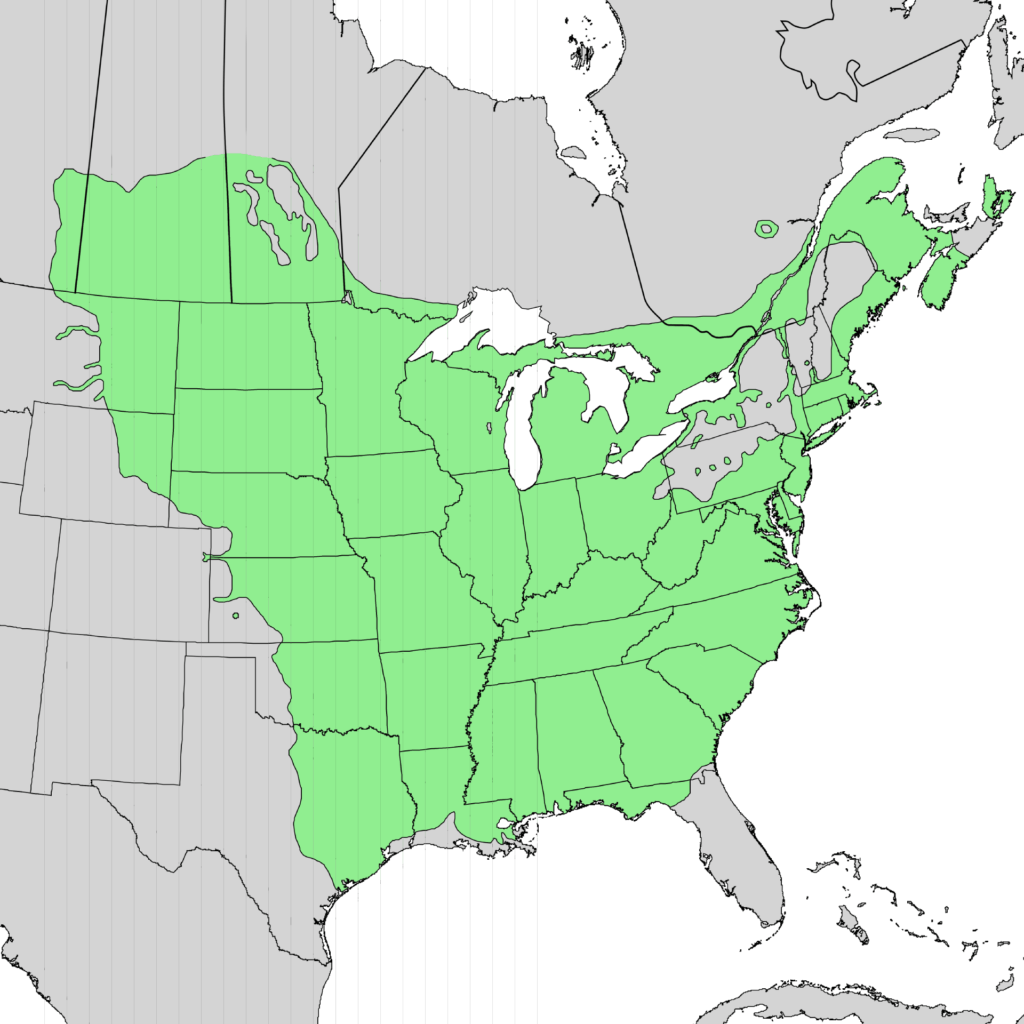

First discovered in Michigan in 2002, the Emerald Ash Borer has caused the destruction of almost all Black Ash trees and is moving south rapidly, destroying all Ash trees in its path.

Several years ago I noticed some of our Green Ash trees dying. Later, I learned that the Virginia Department of Forestry was no longer recommending planting Green Ash along streams. Too bad; Green Ash was one of my “go-to” trees along hundreds of miles of streamside buffers when we fenced cattle out of streams during my tenure at USDA. It was a first-string player in our restoration of the streams that feed the Chesapeake Bay. It’s one of the fastest-growing riparian trees and is one of the first trees to emerge from a tree shelter. But no more. The Emerald Ash Borers are killing the trees.

How the Borer Kills the Tree

The adult Emerald Ash Borer lays her eggs in the crevices of the bark. When the eggs hatch, the larvae bore into the cambium layer of the tree and consume the tree’s vascular system, thus preventing the tree from transporting nutrients and water.

Dead mature Green Ash trees along Trimbles Mill road in Swoope, Virginia. Photo by R. Whitescarver, 7/19.

I Lament Its Demise

In a single lifetime, Ash trees will be gone from the landscape as we know it. Like the American Chestnut, once the greatest tree in America, whose population was minimized by a foreign fungus, and the Eastern Hemlock, being killed by the Adelgid Aphid, the Ash’s population has been brought down by an invasive, foreign species.

I feel a sense of hopelessness in our never-ending struggle with invasive species. Has invasiveness joined so many other human induced vectors on the exponential growth curve, also known as the Malthusian “J” curve? Human population, atmospheric CO2 concentration, extreme weather events, algae blooms … invasiveness—it seems like exponential growth to me.

Hope for a Remnant Population

But we cannot give up. With hope, dedication, and science we can ovecome the devestation from the lack of Ash trees. Like the invasive Musk Thistle population on our farm, we have it under control. And like the American Chestnut tree, there are dedicated scientists, foresters, and volunteers that keep planting seeds of hope that one day the tree will be restored to a sustainable population.

We have hope that we can sustain a remnant population by using systemic insecticide treatments, biological controls, and selecting for trees with high tannin content. Ash species with high tannin content are resistant to the borer.

Diversity Is the Key for Sustainability

The lesson in all this is that a diversity of native trees is paramount for forest and stream health. Diversity is the key to sustain just about everything. Dr. Bern Sweeney, Distinguished Research Scientist at the Stroud Water Research Center recently wrote, “The destruction caused by the Emerald Ash Borer is a wake-up call that we ought to value each and every species in our forest and avoid any and all carelessness that might lead to the demise of any given species. For the loss of each species in a forest is analogous to death by a thousand cuts for the ecosystem.”

The Answer—Plant More Trees

The video below, produced by The Downstream Project for the Chesapeake Bay Foundation shows the importance of planting trees along streams and features the late Libby Norris.

The post Ash Trees—a Celebration and a Lament (JMU 2020) appeared first on Getting More on the Ground.